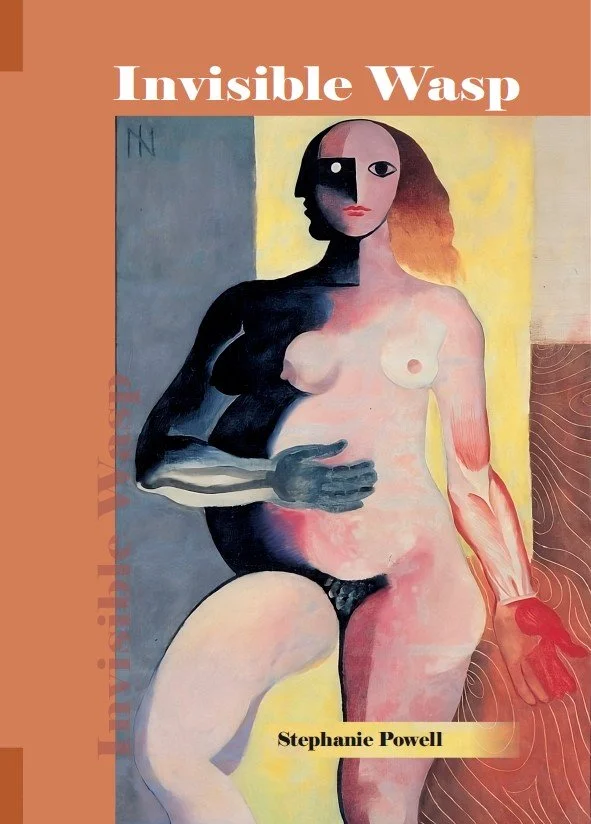

Invisible Wasp by Stephanie Powell

Invisible Wasp (2024, Liquid Amber Press) is Australian poet Stephanie Powell’s third poetry collection, and offers an introspective and sensuous meditation on being alive. The poems within are sticky, visceral and personal, exploring sex and desire; the camaraderie and challenges of girlhood; doctor’s appointments and the body; mental health, fertility and pregnancy. Powell’s world is one in which everything is familiar yet strange, and always on the brink of shapeshifting under the weight of experience.

Divided into two parts – ‘Laughing or dying, whatever’ and ‘Flate’ – the collection arcs from adolescence to motherhood, moving from memories of youthful yearning towards a more mature, if no less uncertain, reckoning with the body and its transformations.

Part one takes its title from a line in ‘Paris, Christmas 2016’, as the narrator is looking back at the detritus of girlhood with some nostalgia, but also a shrewd and humorous eye:

“Between rods of grey light

the debris of our twenties –

wet wipes, makeup tubes

scrunched knickers, all glittering

trash, all anchorless as we are.”

The performance of young womanhood is something Powell is preoccupied by – how beauty and desire can be at once a source of power, as well as a trap. In ‘We are young and delicious’, the girls want to be like “the girls in Dolly with the / thoroughbred manes and pin-drop legs.” She writes:

“Sometimes we take the train into the city

To sit in Fed Square

and undo our top buttons.

Tell the men who come

We are young and delicious, young and

Delicious, when our youth doubles as a blessing and

an injury.”

The flirtation with danger here is palpable – men are something to be desired, and feared – while the double standards for girls are brought into sharp relief. In ‘In class,’ the narrator is shamed for having “left my legs open, cotton triangle visible,” and this feeling is made manifest in the shape of the poem itself: a down-turned triangle.

I love the way Emilie Collyer describes the “everyday erotic” of Powell’s poems and their “slippery intimacy”. Ordinary details and objects are enlivened through the poet’s rich and careful observations:

“A tired pen / Tallying a week’s shopping, the knife / That slips between the gum of an envelope.”

Many poems are saturated and cinematic, like a Wong Kar-wai film. Indeed, one poem is inspired by Chungking Express, and much of the collection has that same fragmented, luminous atmosphere. My favourite of the bunch is the prose poem ‘Touch free wash’, an evocative nocturnal vignette:

“An un-beautiful place looked at differently, luminant in neon and the feeling of God watching the CCTV. The Servo. Tonight, capturing me in depression clothing and sandals in winter, I have come for the empty calories and to read newspaper headlines.”

Powell is at her best when writing about the impersonal invasiveness of doctor’s clinics – especially the body’s vulnerability, as borders between internal and external are crossed, and she feels both porous and exposed. In ‘‘Maybe, baby,’ a fertility clinic is evoked in all its Plath-like horror:

“knickerless under the paper skirt

i couldn't do without a baby

the instrument tickled thighs to

quaking when the doctor probed

then wrote for the blood test

i slid my feet from the stirrups

and put my clothes back on

stapled by the shame of

occupying a body marked for

incisions and internal stitches -

more exorcisms, cold and

clinical, held in brightly lit rooms”

In the second part of the book, ‘Flate’, our narrator is experiencing pregnancy as a somewhat disorienting physical and psychological state. Flate – a word I was unfamiliar with – means ‘the feeling or experience of nausea.’ As she is coming to terms with her new liminal sense of identity, she “tries not to dissolve,” yet “the rooms are liquifying / and will not regain their shape.”

However, in ‘Ultrasound reports,’ the beautiful, radiant description of seeing her baby for the first time offers a counterpoint to the discomfort of previous medical experiences. Even though she is “bare bottomed on the gurney / knees broken open” the vision is cosmic, euphoric:

“The sonic path to your fish body ignites

and recedes many times in seconds

each turn of the wand a new valley of moon

and I cup my hands behind my head for a

better angle, the viewpoint of a glassblower

watching your mass expand and balloon away.”

Overall, Powell’s collection is intense, intimate and surprising. Like the invisible wasp of the title, her poems hum with lyricism, and are capable of delivering a sharp, careful sting.

Emily Riches is a writer and editor from Mullumbimby, currently living on Gadigal land (Sydney). She founded Aniko Press to bring passionate writers and curious readers together, discover new voices and create a space for creative community. Get in touch at emily@anikopress.com.