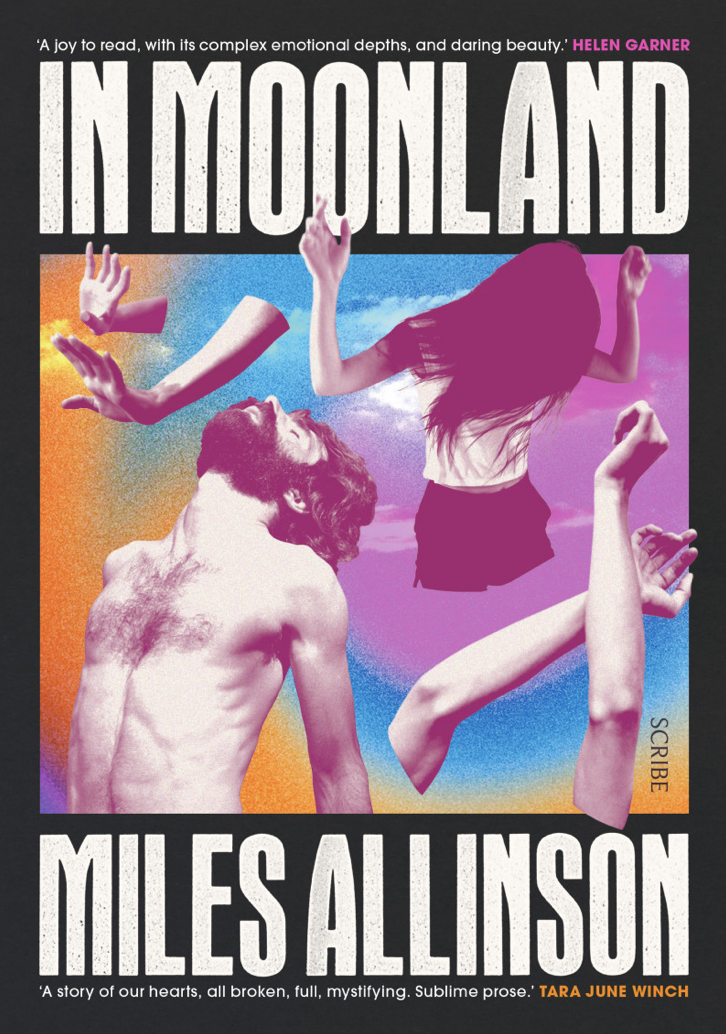

In Moonland by Miles Allinson

In Moonland (2021) is the long-awaited second novel from Miles Allinson, whose debut, Fever of Animals (2015), won the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for an Unpublished Manuscript. In Moonland is similar to its predecessor with its immersive writing style, themes and gripping characters, yet it gives space to fresh ideas and a very original narrative. Fatherhood, masculinity, mortality and familial mythologies are explored in four parts over very different settings: from contemporary Melbourne, 1970s India, to a climate-ravaged dystopian future.

The book starts with the beginning and the end of life: in Melbourne, our narrator Joe welcomes the birth of his daughter, while also being preoccupied by the death of his father, Vincent. Joe still struggles with his father’s apparent suicide, twenty years after the fact:

“But what does it mean to live for a while and then kill yourself one Friday just because you feel like it?”

This question echoes throughout Joe’s narration. In an attempt to better understand the man that played a distant yet pervasive part in his life, he decides to leave behind his own struggling young family to embark on a journey to India. This quest is sometimes crazed and sometimes half-hearted – for all his preoccupation with his father’s death, he keeps putting off the inevitable, as if afraid of what might come to light. Assessing the life and shortcomings of Vincent this way also brings into focus the ways in which Joe himself is failing as a father and how family trauma can be passed down from parent to child like an heirloom.

In the second part, we get a glimpse into the life of Vincent as a young man, as he joins the ashram of real-life Indian religious leader Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh in the hope of finding truth and salvation. Vincent is young and fallible: on the run from his old life and seeking something even he can’t quite put his finger on. While his story is mostly focussed on his time at the ashram, something dark and heavy looms over him, later resulting in his return to Australia. It is in this darkness that we get to see what Vincent is struggling with, and how intergenerational trauma often manifests in violence.

To be exposed to Vincent’s experiences as a young man and Joe rushing to put the pieces of his family history together, Allinson explores deeper complexities in masculinity and family relationships, particularly between parents and children:

“A parent’s love for a child, you probably know this yourself, it’s pretty bottomless. It goes down into the guts of the world. But a child’s love for a parent is different. It goes up. It’s more ethereal. It’s not quite present on the earth.”

In his efforts to find out more about his own father, Joe neglects all fatherly duties and becomes a completely different man himself. This has lasting and obvious effects on his daughter Sylvie, perpetuating the cycle of abuse started generations before them.

In the last two parts, In Moonland takes a turn towards dystopia. In a climate-ravaged landscape, Sylvie visits her father for the first time in years, faced with a life-altering decision. This conclusion to the book is, in a way, inevitable – and while the end of the novel is depressing and foreboding, Sylvie’s presence and her decision inject a sliver of hope into the narrative – maybe she will be the one to break the cycle.

By and large, it’s not very often that you read something that feels both entrenched and fresh – and In Moondland is exactly that. At a time when literary fiction seems to have fallen down a rabbit hole of similar tropes – dominated by self-assured, deeply damaged young women on a quest to find themselves at any cost – In Moonland stands out in more than one aspect. To step out of the known and abandon those literary tropes is daring. And In Moonland is nothing if not daring.

Allinson’s sharp and skilled prose lends In Moonland an authority that’s hard to find elsewhere – this is a book that can show you something new, unfurling in an experience both dazzling and confronting. It grabs you by the throat and doesn’t let go until the very end.

Fruzsina Gál is an aspiring writer, born in Hungary but living in Australia. She has been a reader all her life, and her first short story, 'The Turul' was published in Griffith University's 2018 anthology, Talent Implied. Her writing is often focussed on identity and the effects of immigration on the self. You can find her online at www.fruzsinagal.com or @thenovelconversation.